“It is a magnificent plant and it represents, at once, a great hope and great disappointment” – Stanley Frank, New York Post Sports, 2nd of March 1942.

Originally devised and developed in 1940, under the new Fulgencio Batista government, Parque Deportivo José Martí was a sign of hope and things to come. The facility gifted the children of Havana a sport and recreational space never before dreamt of in Cuba. Almost a of symbol of the Batista government itself, 1940 was a time of great excitement and optimism in Cuba, physically manifested in the ambitious architecture and intended use of the park.

The following two decades saw the eventual demise of Batista, increasing governmental involvement with corruption, political and social unrest throughout Cuba. Throughout the 1950s, Fidel Castro and Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara set out to bring change to the country, a revolution unrivalled in recent history.

When Castro officially took power in 1959, it was only a matter of months before Parque José Martí was again given due attention, with architect Octavio Buigas designing what would become the focal piece of the park, the grandiose grandstand. This strong architectural form in the landscape reflected the current post-revolutionary architectural and political tides taking place in Cuba. It’s looming structure facing the Malécon and on towards the Atlantic Ocean, a mere stone’s throw away.

In 1971, Havana’s other large sports stadium, Estadio Latinoamericano was given a major refurbishment and expansion. In 1989, Estadio Panamericano was built to host the 1991 Pan American Games. With the major investments being made to these sporting arenas, Parque José Martí became largely forgotten.

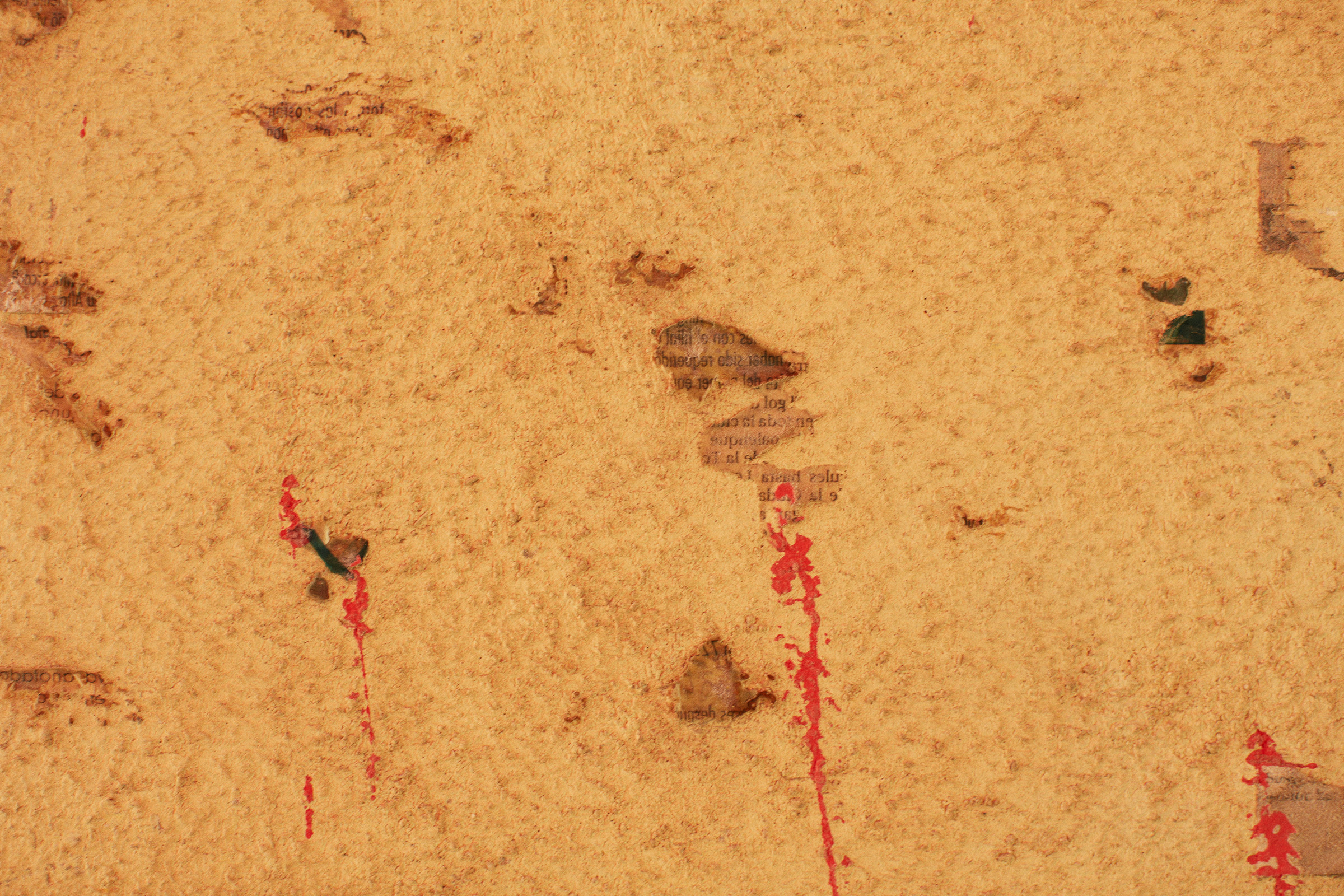

Today, with Cuba on the brink of the biggest social reform since the late 50’s, Parque Deportivo José Martí stands proud, but in a state of forgotten dilapidation, and it’s history, as well as the park itself, mysteriously missing from many maps and guide books. The once magnificent structures have been subject to an abundance of graffiti, and many areas fenced off with severe safety concerns. ‘Derrumbe’ (meaning collapse) can be seen scrawled across the faded walls.

Yet the colours and textures hark back to the park’s heyday. Layers upon layers of history can be felt in the faded peeling paint, where stories and sounds are hidden around every corner. Most significantly, this politically forgotten space is anything but forgotten. Beyond the crumbling concrete and flaking paint, a spirit that can not be contained shines through, the passion and unity of the Cuban people, embracing every square metre of the overlooked land for the exact purpose it was intended for, sport and recreation.

The opening quote, written by Stanley Frank for the New York Post Sports on the 2nd of March 1942, is as true today as it was the day it was conceived. More so, it has been true at moments in time since the site was established. The hidden history of the park is almost a mirror for Cuba itself.

Scroll to top